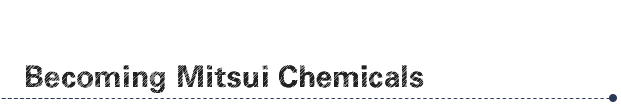

The Mitsui Chemicals Group traces its roots back to 1912 and the Mitsui coal mines in Kyushu.

From 1912, when we first started operations in Omuta, coal chemicals were one of the cornerstones of Mitsui’s chemical operations and remained so until the transition to petrochemicals around 1960. In this issue, we take a closer look at the history of synthetic indigo dyes and synthetic ammonia, both which were central to our chemical operations.

-

Coal made a huge contribution to industrial development from the 19th century through to the first half of the 20th century, as an alternative source of thermal energy to wood and charcoal, and also played a pivotal role in the development of the chemical industry. Carbonizing coal at high temperatures produces coke and coal gas, leaving behind coal tar as a by-product. Coal chemicals began with the extraction of aniline, a dye made from coal tar. That paved the way for other products that formed the basis of the chemical industry, including synthetic ammonia, plastics, and solvents such as benzene and toluene.

-

Mitsui’s coal chemical operations date back to the completion of the first Koppers coke oven in Omuta in 1912. The company started operating coal tar distillation and gas plants at the same time, along with an ammonium sulfate plant, which began recovering ammonia from gas produced by the coke oven in order to react it with sulfuric acid and produce ammonium sulfate. These were the first steps towards our modern-day chemical operations. Having successfully established domestic production of the synthetic dye alizarin, the company set about expanding its chemical operations. Nothing symbolized this better than the successful synthesis of indigo, the so-called “king of dyes”. This completely transformed Mitsui Coal Mine’s business, which had previously relied on profits from coal.

With demand for chemical fertilizer in Japan increasingly shifting towards synthetic ammonium sulfate, the company decided to branch out into areas such as synthetic ammonia and ammonium sulfate, and even began producing synthetic methanol. Alongside its synthetic dye operations, the Omuta Works evolved into a substantial coal chemical complex.

Production of items such as synthetic dyes, explosives, and pharmaceuticals continued to increase during the war, for military use. The company commercialized synthetic rubber and also moved into the synthetic petroleum business.As demand for chemical fertilizers soared in response to postwar food shortages, the company built a new plant in Hokkaido and began mass-producing urea.

The focus of the company’s operations later shifted to other areas such as natural gas chemicals and petrochemicals.

Coke Coal Plant at Mitsui Coal Mine’s Miike Dye Works (1926)

Coal cooled with water after coming out of the Koppers coke oven

![]()

Indigo epitomized Mitsui’s chemical business. After starting production, operations continued to change in line with shifting trends. Here we look at the history of indigo, from its development through to the end of production 65 years later.

-

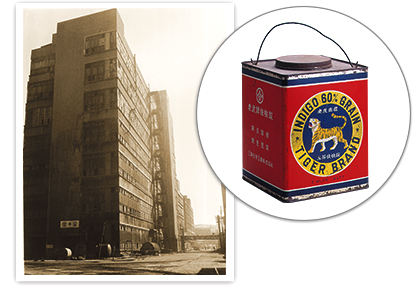

The L Plant, completed in 1934. It was followed by the V Plant (indigo) and a string of other high-rise dye plants, which seemed to pop up like skyscrapers(Left)

Cans of Tiger Brand indigo which soon became popular on the export market(Right)

Having successfully industrialized the red synthetic dye alizarin, it was inevitable that Mitsui Coal Mine would move on to research and development of indigo.

Synthesizing indigo, however, required a considerable amount of research. The fact that research got underway in 1913, at the height of World War I, also meant that it was impossible to draw on German technology. Relying instead on existing documents, Mitsui was the only company to continue with research. Research was also spurred along by rivalry with the Sumitomo Group, which was conducting government-subsidized research into synthetic dyes.

In the face of criticism from management of the Mitsui Coal Mine, who were concerned about “squandering profits from coal”, Mitsui executive Takuma Dan remained focused and determined. “I believe that dyes represent the next generation. While we have achieved much, it will take time until we start to make a profit.” Dan quashed any opposition and proceeded to perfect indigo. Production got underway in 1932. -

Indigo color samples, best known for use in jeans (Process Technology Center in Mobara)

Success with indigo production completely transformed feelings towards chemicals within Mitsui Coal Mine, resulting in a substantial increase in production. Having produced 695 tons of indigo in 1934, the company began exporting to China the following year. By 1937, production was up to 980 tons.

Shifting to wartime operations however brought things to a standstill. Production slumped to 57 tons in 1943 before halting altogether. Although damaged plants were quickly rebuilt after the war, factors such as the diversification of clothing prevented demand from growing and kept annual production at around 300 to 400 tons throughout the 1950s and 60s. Despite being one of Mitsui’s flagship chemical products, indigo had to wait until the jeans boom of the 1970s for any real increase in production. -

Indigo condensers, which were used since production first started (1992)

The denim boom took hold in 1976, sending demand for indigo soaring. Having expanded production facilities to keep pace with current trends, the company increased annual production to 800 tons, and again to a maximum of 1,100 tons in 1981. The introduction of new equipment such as alkali condensers and spray dryers enabled production to be increased even further, all the way up to 1,450 tons.

Unfortunately, Mitsui’s manufacturing methods couldn’t compete with those in Germany, in terms of raw material, production efficiency, or cost. Companies producing indigo at far lower prices started to appear in China too, resulting in a gradual loss of competitiveness. Production was suspended in 1997 and plants closed down in 1998. 65 years of indigo production came to an end. -

Indigo is one of the oldest dyes in the world. As it has such a wide range of uses, it has been prized as the king of dyes since ancient times. Prior to its popular use in denims, the color was widely used in Japan (“ai” in Japanese). The name indigo comes from India, which is where natural indigo is produced.

Whereas most natural indigo comes from a tropical plant called anil, the vast majority of the indigo used today is chemically synthesized.

![]()

In addition to indigo and other synthetic dyes, Mitsui began manufacturing synthetic ammonia and ammonium sulfate, creating a coal chemical complex capable of producing a comprehensive range of chemical products.

-

As part of the company’s coal chemical business, Mitsui Coal Mine branched out into synthetic ammonia in 1928. It all started with the acquisition of operations from general trading company Suzuki Shoten.

Having acquired the patent to technology for synthesis of ammonia using the Claude process in 1921, Suzuki Shoten constructed a plant in Hikoshima, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in 1924. As business conditions deteriorated following the end of World War I however, the company collapsed. The Bank of Taiwan had close ties to Suzuki Shoten and also collapsed as a knock-on effect. Mitsui Coal Mine was asked by the Bank of Taiwan to buy Suzuki Shoten, as a means of recovering loans receivable. Mitsui Coal Mine Managing Director Tamaki Makita rejected the request. He explained to Fusanobu Isobe, President of Suzuki Shoten group company Daiichi Nitrogen, that even though the company had carried out ammonia synthesis testing, its scale of production was just too small. He offered to buy the company for scrap instead. Realizing that he had little choice, Isobe backed down and asked if they could come to some arrangement. As a result, in 1928 Mitsui took over the lease free of charge and began running the company on a voluntary basis.Having conducted preliminary studies with an eye to entering the synthetic ammonia and ammonium sulfate business on a larger scale, Mitsui officially acquired the company in 1929 and took over the Hikoshima Works (now Shimonoseki Mitsui Chemicals).

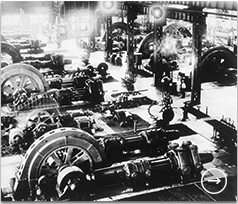

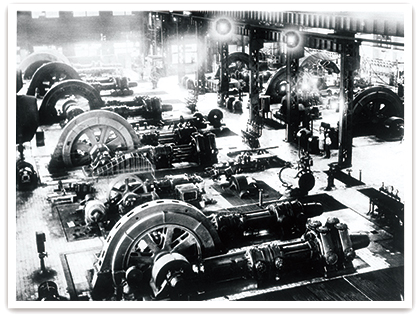

Ammonia gas compressors at Toyo Koatsu Industries’ Omuta Works

-

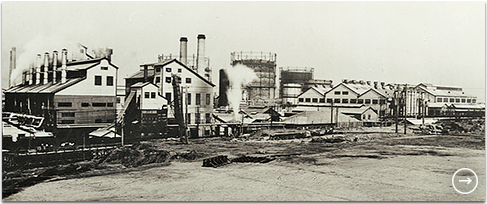

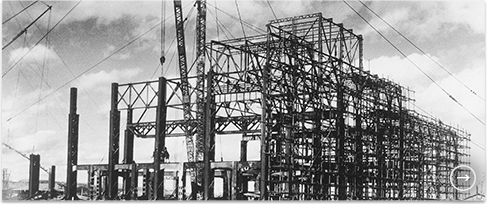

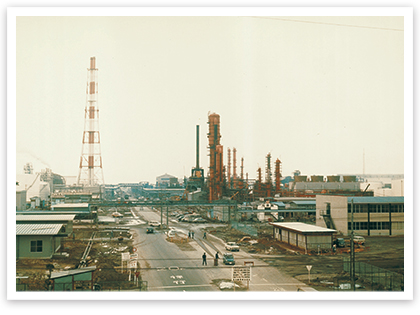

Toyo Koatsu Industries Omuta Works (1934)

Hikoshima Works played a key role in the postwar recovery of Toyo Koatsu Industries

Around the same time that the company started producing indigo, demand for ammonium sulfate was also soaring. In 1933, Mitsui took advantage of a government incentive scheme to establish Toyo Koatsu Industries. In order to increase production of ammonium sulfate, the company built a large-scale ammonia plant, capable of converting raw materials into efficient coke, next to the coke oven in Omuta. The establishment of this new plant gave Mitsui Coal Mine added confidence. “For a company such as ourselves, capable of maintaining low production costs thanks to outstanding manufacturing methods, it should be relatively easy to use our spare domestic supply capacity to expand into other countries.” Demand for chemical fertilizer was increasingly shifting to synthetic ammonium sulfate around that time, and conditions were falling into place for domestic production. The establishment of Toyo Koatsu Industries, and the merger of synthetic operations with Miike Nitrogen, which had been set up to handle synthetic ammonia and ammonium sulfate, helped pave the way for a more comprehensive range of coal chemical operations on a larger scale. Just as the coal chemical complex in Omuta was at its peak however, Japan plunged into World War II. Mitsui Chemical Industries was established in 1941, during wartime operations. Instead of ammonia and ammonium sulfate, it prioritized production of nitrates for use in explosives.

-

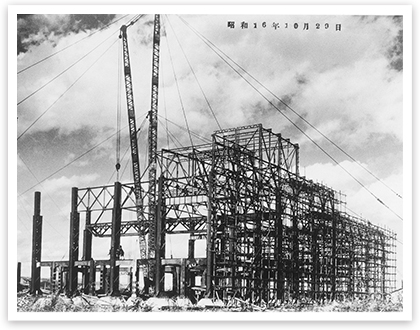

Synthetic Ammonia Plant at Toyo Koatsu Industries’ Hokkaido Works during construction (1941)

After the war, a national policy was set out to increase production of chemical fertilizer, in an effort to tackle food shortages. To achieve that goal, it would be necessary to increase production of ammonium sulfate. As there was a shortage of the raw material sulfuric acid however, the only viable alternative was the mass production of urea, a synthetic fertilizer made from ammonia and carbon dioxide.

Toyo Koatsu Industries responded by building the world’s first mass production urea plant in Hokkaido in 1948 (now Hokkaido Mitsui Chemicals). The company was already producing urea in Omuta and Hikoshima, but costs were starting to hamper production. Realizing that building a facility capable of producing large volumes would enable it to produce urea for more or less the same cost as ammonium sulfate, the company set about constructing a plant in Hokkaido. It also improved manufacturing processes in Omuta and in 1950 installed urea manufacturing facilities. It took a lot of hard work, even at the Hikoshima Plant, which had escaped damaged by the war, but installing and expanding new facilities played a key role in the recovery process.

That was how Toyo Koatsu Industries managed to grow into a major chemical fertilizer manufacturer in just a short space of time. -

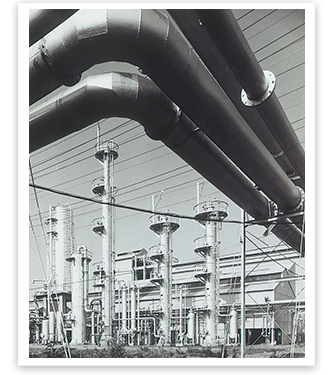

Gas scrubbing towers at Toyo Koatsu Industries’ Chiba Works, newly constructed as the company branched out into natural gas chemicals

In an effort to cut costs during the postwar recovery years, the chemical fertilizer industry in Japan moved towards gas as a less expensive source of raw materials. As a result, companies came under pressure to reconfigure their fertilizers and install larger facilities. On a global scale too, manufacturing was switching from coal and coke gasification in favor of crude oil or heavy oil gasification and natural gas gasification. Keeping pace with such trends, Toyo Koatsu Industries similarly made plans to build a new plant at Mobara, Chiba prefecture, with an eye to switching to natural gas (now Mobara Branch Factory). The company started work on gas field development and began building production facilities. Production of ammonia and urea got underway in 1958.

-

Ammonia Plant at the Osaka Works

As Japan’s rapid economic growth continued, facilities continued to expand in scale during the latter half of the 1960s. In 1969, the company completed a plant capable of producing 1,000 tons of ammonia and 1,750 tons of urea at its Osaka Works (now Mitsui Chemicals’ Osaka Works).

In 1961, the engineering wing of Toyo Koatsu Industries broke away to become Toyo Engineering, in order to accelerate exports of urea technology to the world.

Through Toyo Engineering, a total of 147 plants in 30 different countries currently use licensed urea technologies based on Mitsui Chemicals technologies (as of March 2010). We intend to keep on rolling out our technologies to other countries in the future.

The petrochemical industry developed as an essential part of Japan’s postwar recovery and economic growth.

-

Despite a temporary loss of momentum, chemical products revolved primarily around coal-based chemical fertilizers and inorganic chemicals such as soda after the war. Before long however, petrochemical products developed in the US, including synthetic resins (plastics), fibers, and rubbers, were imported to Japan and increasingly became the mainstay. The discovery of oil in the Middle East ushered in an energy revolution, as the industry switched from coal to oil. Domestic oil supplies also increased.

Around this time, the Japanese government was looking for a more open economic framework, through measures such as deregulating trade and capital. It earmarked domestic industry as a top priority and set about promoting major growth in the electric, electronic, and automotive sectors. Strengthening domestic production of raw materials was a key national strategy to promote industry.

In terms of technology, advances in polymer chemistry in Europe and the United States triggered a fullscale technological revolution. The conditions were in place to secure stable oil supplies and establish domestic production of petrochemical products.

Commercializing petrochemicals required highly economical, low cost raw materials. Exhaust gas from oil refineries was eyed as a possible source. As Japan’s oil refineries were relatively small scale and did not produce much gas however, this proved to be economically unviable. Instead, the decision was made to use naphtha left over from gasoline refining processes.The whole concept of harnessing surplus resources has a lot in common with the early days of the coal chemical industry and its use of by-products from coke ovens. Existing expertise from the coal chemical industry also played a key part in developing chemical manufacturing technologies, constructing plants, and designing large-scale industrial complexes. The chemical industry made the petrochemical industry a reality.

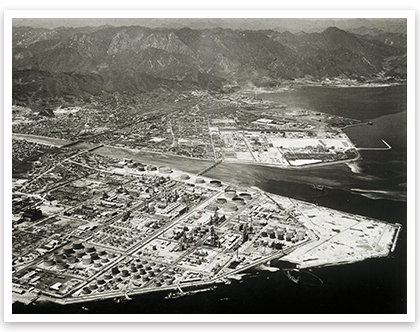

Birthplace of the petrochemical industry Iwakuni-Ohtake Works (1962)

-

Use of oil as a raw material for chemical products began in 1920. Standard Oil is thought to have been the forerunner when it started manufacturing isopropanol from propylene in the US. Being a liquid, oil was easier to transport and cheaper to handle than coal, which had been used as the main raw material in chemical products prior to that point. Technology developed rapidly as a result. Whereas Japan uses naphtha (crude gasoline) as a raw material, the main raw material used in oil producing countries in the Middle East, and in countries such as the United States and Canada, is ethane, which is found in natural gas and gas produced when extracting oil. Currently, most chemical products are made from oil and it continues to play a central role in the development of our society.

-

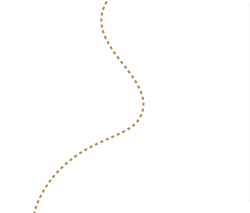

Dr. Ziegler giving a technical explanation at Mitsui Chemical Industry (1956)

Ziegler-processed polyethylene technology formed the cornerstone of the Mitsui Chemicals Group’s petrochemical operations. In 1954, Mitsui Chemical Industry President Ken Ishida was introduced to the research of Dr. Karl Ziegler during a tour of Europe and the United States. In his writings, Ishida described the experience as “a completely unexpected turn of events…”

Ziegler-processed polyethylene products had an exceptionally high molecular weight, without necessarily having to use high-grade ethylene as a raw material. Convinced that this was the future, Ishida decided to acquire the patent, and in 1955 signed an option agreement. The exclusivity fee came to US$1.2 million (432 million yen). The company pooled its resources and assembled a team of around 100 researchers and began working on industrialization. Trial production was a success and got underway in 1956, producing ten tons a month. At the same time as developing expertise in manufacturing machinery and methods, the company also set about establishing a market. -

Establishing a domestic petrochemical industry required massive capital investment. As individual Mitsui companies could only achieve so much on their own, the idea of combining their strengths gained momentum. During this time, the Japanese government set out measures to promote the petrochemical industry, in an effort to establish a more sophisticated industrial structure and enhance international competitiveness. Chemical companies began revising business plans.

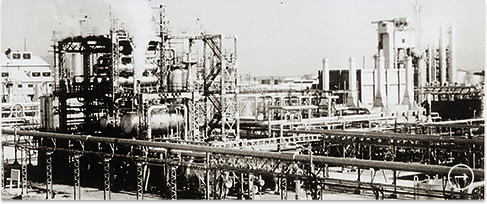

Against this backdrop, Mitsui Petrochemical Industries (MPI) was established in 1955 through joint investment of eight companies, namely Mitsui Chemical Industry, Toyo Koatsu, Miike Gosei, Mitsui Mining, Mitsui Kinzoku, Koa Oil, Toyo Rayon, and Mitsui Bank. The company secured a 319,000m2 site, in the form of a defunct army fuel depot in Iwakuni, and began preparations with a focus on bringing in overseas technology. In April 1958, work on Japan’s first comprehensive petrochemical complex was completed and production got underway. Having transferred from Mitsui Chemical Industry to MPI after the establishment of the new company, President Ishida’s task was clear. “In taking on the important task of establishing a new company, with advice from the government, financial institutions, and other related industries, we intend to make a serious contribution to Japan’s economic development.”As well as pride in paving the way for the future of the petrochemical industry in Japan, MPI was built on cooperation, as companies throughout the Mitsui Group joined forces.

Group photo at the inaugural meeting on July 1, 1955 (President Ishida is fourth from left in front)

The period from 1955 to 1964 was the era of domestic petrochemical production, as Japan began to experience rapid economic growth.

The Mitsui Chemicals Group played a crucial role in the development of the petrochemical industry in Japan.

-

HI-ZEX film

Technology to manufacture polyethylene was licensed from Mitsui Chemical Industry to MPI in 1956. The company launched HI-ZEX in 1958. Operations were structured so that HI-ZEX manufactured by MPI was sold by Mitsui Chemical Industry. As Mitsui Chemical Industry was conducting ongoing market research and compiling comprehensive production and sales plans, prior to the start of polyethylene production, it made sense to divide up production and sales within the group. Sales were sluggish initially at around 150 to 200 tons per month. The hula-hoop boom of 1958 drove sales to 1,259 tons by November that year. Individual companies within the Mitsui Group worked to expand operations of not only HI-ZEX but other products as well.

-

Japan’s first ethylene plant at the Iwakuni-Ohtake Works (1958)

Celebrating completion of the complex at Ohtake (looking down on the works from National Route 2)

Demand for petrochemical products in Japan continued to grow. The new Cabinet established by Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda in July 1959 set out an “income doubling plan” in December that same year, spurring on rapid economic growth. The government supported development of large-scale petrochemical facilities with the aim of becoming “globally competitive”.

MPI meanwhile launched its Phase II Plan to expand the scale of its Iwakuni Works (now the Iwakuni-Ohtake Works). As there was limited land available on the company’s Iwakuni site, it decided to establish ethylene and new project plants at an adjacent Ohtake site by the Oze River. Construction began in 1961 and continued through to 1963. By the time the works was finished, it had a total area of approximately 924,000m2.

As demand continued to soar, MPI launched a Phase III Plan, aimed at streamlining the works. The petrochemical industry was transforming from domestic production to a new era of large-scale facilities.

![]()

Petrochemicals became the driving force behind the chemical industry in Japan. As facilities continued to grow in scale, domestic demand began to reach maturity. In Chiba and Osaka new works rapidly emerged.

-

Chiba Works (1970)

Personnel setting off from Iwakuni for Chiba (1966)

Eagerness to invest in Japan’s petrochemical industry showed no signs of slowing, even during the recession from 1964 to 1965. With no room to build more plants at its Iwakuni-Ohtake Works, MPI made plans to construct in Chiba. Just a stone’s throw from Tokyo, Japan’s biggest consumer market, Chiba was a prime location in terms of marketing.

As part of plans to develop the Keiyo Industrial Zone, between Chiba and Tokyo, construction got underway in the Goi, Anegasaki, and Sodegaura areas of Chiba prefecture. MPI played its part too. Following land reclamation, civil engineering, and plant construction work, the new Chiba Works (now the Ichihara Works) was completed in 1967.

With a systematic, functional layout, the Chiba Works helped streamline the flow of raw materials and products, and even factored in the need to expand in the future. It was based largely on experience and expertise from the Iwakuni-Ohtake Works, and had an ethylene plant with an annual production of 120,000 tons, the highest in Japan at the time. The fact that it was built as a polyolefin mass production facility right from the start was one of the Chiba Works’ biggest advantages. A great deal of thought went into preventing pollution too, with drainage checked and separated into oily and non-oily fluids via a general purpose oil separator. -

Operations begin at the petrochemical complex in Osaka (1970)

While the Mitsui Group continued with plans for the Chiba Works in eastern Japan, Toyo Koatsu was looking at petrochemical production in western Japan, in the coastal industrial area of Sakai overlooking Osaka Bay. Plans became concrete in 1963 when the company finalized what it referred to as its “Pre-Sakai Plan”, aimed at securing a share of the petrochemical market in western Japan. This led to the establishment of the Osaka Works in 1964.

At the time, numerous companies were looking at production possibilities in western Japan. As well as working on its Pre-Sakai Plan, Toyo Koatsu also teamed up with Mitsui Chemical Industry and General Sekiyu and submitted plans to the government for commercial production of derivatives, primarily via ethylene production facilities with an annual production of 100,000 tons. A petrochemical plan for western Japan had also been drawn up by other companies based in the area, plunging the situation into chaos. The government stepped in however and instructed the two sides to combine their plans into one, in order to rationalize and increase the scale of operations. After reaching an agreement, Osaka Petrochemicals was established in 1965, with investment from Toyo Koatsu, Mitsui Chemical Industry, and Kansai Petrochemical. -

Senboku petrochemical complex during construction

Despite playing a leading role in the Osaka (Senboku) petrochemical plan, Mitsui Chemical Industry started to experience difficulties in the wake of the recession in 1965. With work on large-scale facilities still ongoing, the Mitsui Group needed to restructure Mitsui Chemical Industry in order to keep on expanding petrochemical operations. The government also set annual ethylene production amounts at 300,000 tons, forcing a change in the Osaka Petrochemical’s 100,000-ton plans. Commercial production of derivatives in line with new standards would require massive investment, meaning that the company would have to grow in scale.

Against this backdrop, a merger was agreed upon between Toyo Koatsu and Mitsui Chemical Industry in 1967, leading to the establishment of Mitsui Toatsu Chemicals on October 1, 1968. Having taken on petrochemical operations in addition to Mitsui Chemical Industry’s existing technologies in areas such as ammonia, the move heralded a new start, as one of the leading comprehensive chemical companies in Japan.